Internet-of-things (IoT) apps are so commonplace today that they can contain a wealth of information of their users. From smart light bulbs to refrigerators and washing machines, there’s an app to help control everything in your home. To us forensic examiners, this can be a goldmine in proving the coming and goings of a suspect. Artifacts found in IoT apps can make a difference in finding out the their whereabouts. For instance, smart light bulbs can be put onto a schedule, say on from 5:00PM to 11:00PM. This means you can expect that the bulbs would be on the “on” status, but if they are manually set to “off” that may be significant. Additionally, things like a smart door lock can be used as corroborating evidence, if it holds a log of when it is in the locked position. To explore this, we will look a popular IoT mobile app called Geeni, bundle ID com.merkuryinnovations.geeni.

WHAT IS THE GEENI APP?

The Geeni app serves as an IoT control center for the user’s home. It allows them to control their smart light bulbs, video cameras, and surge protectors. It can change the colors of the light bulbs or set them on a specific schedule. You can also remotely view your video camera and record, screenshot, or set it to alert you when motion is detected. It has additional integrations for their built-in shop and promotional data. They also have a notifications section for things like if a scheduled task has failed, or if a device has logged into your active account.

On the Play Store, Geeni has over 5 million downloads, making it a prolific IoT application. Examiners can expect to see this in the wild on various mobile devices such as tablets and smartphones. Google reports that this application encrypts the data sent between the user and developer in transit, but that location and other personal information is still collected by the app itself. The app receives semi-regular security updates, with the last update being on October 9th, 2024. The most recent version is 4.0.1 as reported on their Play Store page which can be found here.

TEST ACQUSITION IN CELLEBRITE

| Tool | Version |

|---|---|

| Cellebrite UFED | 7.65.0.247 [Educational] |

| Cellebrite Physical Analyzer | 7.62.2.9 |

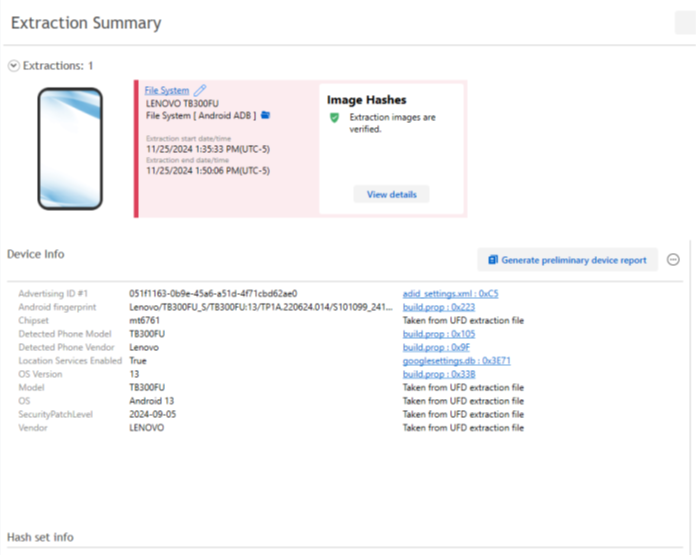

We are using Cellebrite and its suite mobile forensic tools to acquire a full file system image. From this, we can see what kind of information is stored in Geeni. The device used is the Lenovo M8, a tablet marketed for kids but with some decent specifications for $80 USD. This is their 4th generation in the M8 series of tablets and runs on Android 13. The model number is TB300FU. Additionally, it is worth noting that this tablet is capable of being rooted but was not rooted at any point during the acquisition.

Using Cellebrite Universal Forensics Extraction Device (UFED) we were able to make a full file system image of the tablet. For those following along at home, you will need to turn on developer tools by tapping the Android build number 7 times, then enable USB debugging. Pictured above is the extraction summary from Cellebrite Physical Analyzer, which provides an overview of the device post-extraction.

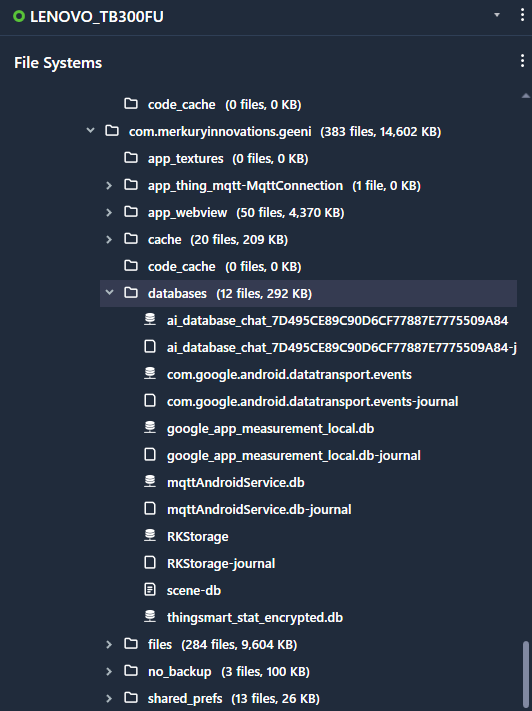

WHAT WAS FOUND?

The Geeni App has several folders that contain a number of databases, javascript files, and .json files. The other miscellaneous files are images and additional cached files from their built-in webstore. There are some databases that are encrypted, but there are some unencrypted ones that provide a good amount of user information.

There appears to also be config files for integration with Tuya Client, an all-in-one IoT platform. Further analysis shows that an XML file contains the email and password for the user account associated with Geeni. It is worth noting that during my analysis, the password string appeared as an authorization token.

/data/data/com.merkuryinnovations.geeni/shared_prefs/KlaviyoSDKPreferences.xml

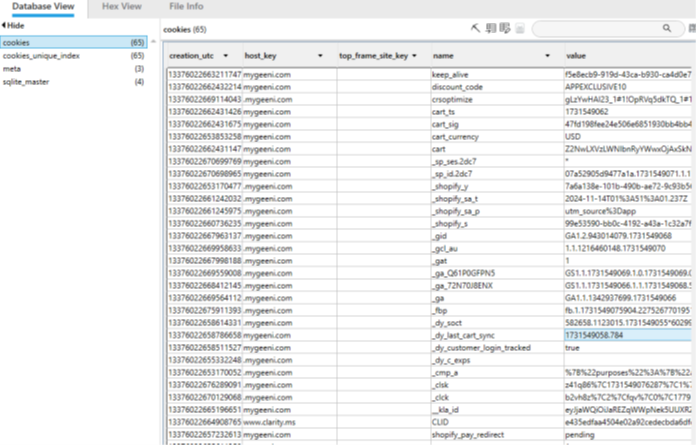

Beyond this, there was not many other personal information that would help identify the user. A lot of the .json and .js files were specific to the storefront, and that seemed to be the majority of the application. Otherwise, the actual functional parts like turning the lights on/off, or Wi-Fi SSID information was either well obfuscated or not available through local files. There were some files that appeared to be logs but could only be viewed with a MMAP system call. These were ultimately files that appeared to generate logs, not the logs themself. The cache folders also did not have anything forensically significant. However, there was a database folder that contained cookies from the webframe utilized by the store. This store would track the user and their cart, syncing a UNIX timestamp for when the app was last opened. While not a “smoking gun”, this could serve as an important piece of evidence showing when the app was last used to control IoT devices.

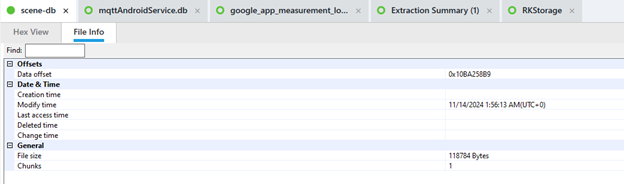

There are two files, scene-db and thingsmart_stat_encrypted.db which appear to have data, but are both encrypted. These are files sent between Merkury Innovations and the Geeni app for things like scene data, the color of the users smart lightbulbs. While the file doesn’t provide much information on their own, some of the metadata provides a modified time, which can help identify when the Geeni app was installed. Several of the databases have SQLite queries, but nothing significant in the file itself.

CONCLUSION AND FURTHER THOUGHTS

Overall, the Merkury Innovations Geeni app provided a good amount of forensic evidence that could help support other findings during a mobile device examination. It does not hold significant enough on its own to yield a critical piece of evidence to a case. This could be taken a step further using a test image that contains information with the Merkury video cameras, or viewing data from the integration into Tuya. This may provide additional artifacts that may be of forensic value.